Fitting the Data

Fitting of the spectra involves selecting a spectral line of interest

(e.g. 195.119 Å) from one of the spectral windows of in the data,

choosing a function (or combination of functions) to fit, and

determining an initial guess for each parameter. The next ingredient for

a fit is the selection of an optimization method. By default, EISPAC

uses a Python implementation of the well-known IDL method MPFIT,

which solves the non-linear least squares problem using the Levenberg-

Marquardt algorithm. The Python module, mpfit.py, is included in EISPAC

and the orginal source code can found on GitHub [1]. Future versions of

of EISPAC may include support for other fitting packages such as the newer

astropy.modeling framework.

Template Files

In order to make fitting quick and easy, we’ve created a set of fit

templates for different spectral lines. Each template consists of one

or more component Gaussian functions and a constant background term.

Template files are named according to the following pattern:

{primary spectral line}.{number of Gaussians}c.template.h5. 119

templates are provided with EISPAC, covering all of the commonly observed

spectral line combinations.

The easiest way to browse and copy fit template files is to use the

eis_browse_templates GUI tool included with EISPAC. This tool can be

used to display a list of all templates available for each spectral window

in an EIS observation and copy the template files to your work directory

(see the eis_browse_templates section for a few tips). A similar result can be

obtained with the match_templates function, which takes either

an EISCube or the path to a header file and outputs a list

(or list of lists) of all fit templates available for a given spectral window

(or data file).

>>> import eispac

>>> data_filename = 'eis_20190404_131513.data.h5'

>>> data_cube = eispac.read_cube(data_filename, 195.119)

>>> template_list = eispac.match_templates(data_cube)

>>> for file in template_list:

>>> print(file.name)

fe_12_195_119.1c.template.h5

fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5

fe_12_195_179.2c.template.h5

In the example above, notice how both one and two component fits are available for the same line. Furthermore, as with many multi-component templates, the third template file is actually a duplicate of the second template, just with the name of the secondary spectral line in the filename. This was designed to make it easier to see exactly which spectral lines can be fit. However, it also means you cannot simply loop over all template files available for a given spectral window, as you would be unnecessarily multiplying the amount of fitting performed (and resultant output files).

We recommend copying the template files you wish to use to your project directory so you have a more self-contained record of your fitting process. Assuming you are running Python from your project directory, the following code snippet illustrates one method you could use.

>>> import os

>>> import shutil

>>> current_dir = os.getcwd()

>>> shutil.copy(template_list[1], current_dir)

Attention

Take care to only copy template files. Moving a template from your

EISPAC installation will lead to incomplete results in future calls

to match_templates().

Loading Fit Templates

An h5dump [2] on one of the template files shows that it contains a

/template group for the initial guess on the fit parameters and a

/parinfo group containing constraints on the parameters for use by

mpfit.

h5dump -n fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5

HDF5 "fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5" {

FILE_CONTENTS {

group /

group /parinfo

dataset /parinfo/fixed

dataset /parinfo/limited

dataset /parinfo/limits

dataset /parinfo/tied

dataset /parinfo/value

group /template

dataset /template/component

dataset /template/data_e

dataset /template/data_x

dataset /template/data_y

dataset /template/fit

dataset /template/fit_back

dataset /template/fit_gauss

dataset /template/line_ids

dataset /template/n_gauss

dataset /template/n_poly

dataset /template/order

dataset /template/wmax

dataset /template/wmin

}

The read_template function can be used to read a template

file and examine the contents.

>>> import eispac

>>> tmplt_filename = 'fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5'

>>> tmplt = eispac.read_template(tmplt_filename)

Use the command print(TEMPLATE) to view a summary of the template, intial

parameter values, and constraints in a nice format.

>>> print(tmplt)

--- EISFitTemplate SUMMARY ---

filename_temp: ./fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5

n_gauss: 2

n_poly: 1

line_ids: ['Fe XII 195.119' 'Fe XII 195.179']

wmin, wmax: 194.9600067138672, 195.25

--- PARAMETER CONSTRAINTS ---

* Value Fixed Limited Limits Tied

p[0] 57514.6647 0 1 0 0.0000 0.0000

p[1] 195.1179 0 1 1 195.0778 195.1581

p[2] 0.0289 0 1 1 0.0191 0.0510

p[3] 8013.4013 0 1 0 0.0000 0.0000

p[4] 195.1779 0 1 1 195.1378 195.2181 p[1]+0.06

p[5] 0.0289 0 1 1 0.0191 0.0510 p[2]

p[6] 664.3349 0 0 0 0.0000 0.0000

The structure of parinfo is specific to MPFIT and should be familiar

to anyone who has used the original IDL version; please see the section

on Constraining Parameter Values for more details. The templates provided

with EISPAC consist of one or more Gaussian functions (with parameters

in the order of peak, centroid, & width) followed by one or more

background polynomial terms (usually just a single, constant value). The

values .template['n_gauss'] and .template['n_poly'] indicate,

respectively, the number of Gaussian functions and background polynomial

terms in a given template.

Note

The multigaussian function is composed of generalized Gaussian functions of the form \(f(x) = A exp(-(x-b)^2/2c^2)\), where A is the amplitude (peak value), b is the position of the center of the peak (centroid), and c is the standard deviation (width). This is consistent with the fit parameters used for EIS data in the IDL SolarSoftWare (SSW) analysis suite.

Custom Fit Templates

EISPAC comes with a wide selection of templates that cover the most common EIS

lines. However, you can also define a custom fitting template for more specific

use-cases. There are two initialization methods available. First, you can call

the EISFitTemplate class directly and pass in the appropriate

values and arrays. Here is an example for initializing a template with a single

Gaussian function and constant background.

>>> new_tmplt = eispac.EISFitTemplate(value=[57514.7, 195.1, 0.0289, 664.3], line_ids=['Fe XII 195.119'])

At minimum, you need to provide a value list or array giving the initial values

for each fitting parameter. The order of parameters is assumed to be sets of

[PEAK, CENTROID, WIDTH] for each Gaussian component followed, optionally, by the

coefficients the background polynomial, starting with the LOWEST (constant) order

term first. If only a value array is provided (as in the example above), the

code will estimate the number of Gaussians and polynomial terms based on the total

number of parameters. Other valid template keys include,

n_gauss (int) - number of Gaussian components

n_poly (int) - Number of background polynomial terms. Common values are: 0 (no background), 1 (constant), and 2 (linear).

- line_ids (array-like) - Strings giving the line identification

for each Gaussian component. For example, “Fe XII 195.119”. If not specified, placeholder values of “unknown I {INITAL CENTROID VALUE}” will be used.

wmin and wmax (floats) - min and max wavelength value of data to use for fitting. Any data in the window outside the range delimited by these two keys will be ignored during fitting.

The following keys are all additional parameter constraints that will be stored

in the .parinfo list of dicts. As such, they must be input as arrays or lists

with the same number of elements as the value array.

fixed (0 or 1) - If set to “1”, will not fit the parameter and just use initial value instead

limited (two-element array-like) - If set to “1” in the first/second value, will apply and limit to the parameter on the lower/upper side

limits (two-element array-like) - Values of the limits on the lower/upper side. Both “limited” and “limits” must be give together.

tied (str) - String defining a fixed relationship between this parameters one or more others. For example “p[0] / 2” would define a parameter to ALWAYS be exactly half the value of the first parameter.

The second method for initializing a custom template is to write a separate

TOML-formatted text file with all of the input parameters and then load the

custom template file using the read_template. This allows you to

save, reuse, and share your templates without needing to copy/paste Python code.

Please note: there is currently no function to export a template from EISPAC and

save it to a TOML file; you will need to create the TOML file yourself using your

favorite text editor. Below is an example TOML file with a copy of the

two-component Fe XII 195.119 template provided with EISPAC.

[template]

n_gauss = 2

n_poly = 1

line_ids = ['Fe XII 195.119', 'Fe XII 195.179']

wmin = 194.96

wmax = 195.25

[parinfo]

value = [

57514.6647, 195.1179, 0.0289,

8013.4013, 195.1779, 0.0289,

664.3349

]

fixed = [0,0,0,0,0,0,0]

limited = [[1,0],[1,1],[1,1],[1,0],[1,1],[1,1],[0,0]]

limits = [

[1,0],[195.0778,195.1581],[0.0191,0.0510],

[1,0],[195.1378,195.2181],[0.0191,0.0510],

[1,0]

]

tied = ['', '', '', '', 'p[1]+0.06', 'p[2]', '']

Assuming this was saved in a file named “custom_fe_12_195.toml”, you can then

easily load it in using the command fe_12_tmplt = eispac.read_template(“custom_fe_12_195.toml”).

For more information about TOML files, please see the

official documentation

Fitting Spectra

Once you’ve read in a template file, you can use the central wavelength

to find the desired spectral window in the data using read_cube.

>>> data_filename = 'eis_20190404_131513.data.h5'

>>> data_cube = eispac.read_cube(data_filename, tmplt.central_wave)

As mentioned in the previous chapter, read_cube automatically

applies all of the pointing and wavelength corrections, bad data

masking, and error estimations needed for scientific analysis. By

default, the code also converts the data from photon counts to intensity

units of erg cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\) sr\(^{-1}\) using

the appropriate pre-flight calibration curve. This conversion can be

disabled by setting the keyword apply_radcal=False, should you

prefer to run your fits in count space.

On to the fitting! Now that you have a template and the data elements,

you can perform a fit of the entire data cube by calling the top-level

fitting routine, fit_spectra. The easiest way to use

fit_spectra is to just give it both an EISCube

and EISFitTemplate object (or filepaths to the data and

template HDF5 files). You may slice your EISCube however

you wish before fitting and the code will loop over the data appropriately

(this includes fitting a single spectra or slit observation). Additionally,

fit_spectra takes advantage of the multiprocessing package

in the Python standard library to automatically parallelize the fitting

process and minimize the run time. You may control the number of

processing cores used for the fitting with ncpu keyword, or set it

equal to “max” or None to use the maximum number of cores available.

Please see the full doc string for fit_spectra for additional

options and parameters.

Attention

Due to the specifics of how the multiprocessing library works, any

statements that call fit_spectra() using ncpu > 1 MUST be wrapped

in a "if __name__ == __main__:" statement in the top-level script

or program. If such a “name guard” statement is not detected,

fit_spectra() will fall back to using a single process. Unfortunately,

this means you can not directly use parallel fitting from an interactive

Python shell, you must first write a program that you save and run.

Here is a minimal example program that just loads and fits the data.

import eispac

if __name__ == '__main__':

# input data and template files

data_filepath = './eis_20190404_131513.data.h5'

template_filepath = './fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5'

# read fit template

tmplt = eispac.read_template(template_filepath)

# Read spectral window into an EISCube

data_cube = eispac.read_cube(data_filepath, tmplt.central_wave)

# Fit the data, then save it to disk and test loading it back in

fit_res = eispac.fit_spectra(data_cube, tmplt, ncpu='max')

save_filepaths = eispac.save_fit(fit_res, save_dir='cwd')

FITS_file = eispac.export_fits(fit_res, save_dir='cwd')

load_fit = eispac.read_fit(save_filepaths[0])

Note

The command line script eis_fit_files can be used to quickly

fit a directory of files using one or more templates in another directory.

EISFitResult Objects

fit_spectra outputs an EISFitResult object,

which may be saved to an HDF5 file and read back in later using the

save_fit and read_fit functions (as shown

in the example above). The output fit parameters are stored in a dictionary

of arrays.

>>> for key in fit_res.fit.keys():

... print(f"{key:<15} {fit_res.fit[key].dtype} {fit_res.fit[key].shape}")

line_ids <U14 (2,)

main_component int16 ()

n_gauss int16 ()

n_poly int16 ()

wave_range float64 (2,)

status float64 (128, 32)

chi2 float64 (128, 32)

mask int32 (128, 32, 24)

wavelength float64 (128, 32, 24)

int float64 (128, 32, 2)

err_int float64 (128, 32, 2)

vel float64 (128, 32, 2)

err_vel float64 (128, 32, 2)

width float64 (128, 32, 2)

err_width float64 (128, 32, 2)

params float64 (128, 32, 7)

perror float64 (128, 32, 7)

component int32 (7,)

param_names <U32 (7,)

param_units <U32 (7,)

We can extract an array of the fit parameters or intensity profile using

the get_params and

get_fit_profile methods. Both methods take

optional keywords for selecting the component number and/or an individual

pixel (using array coordinates). get_fit_profile

also has a num_wavelengths keyword that allows us to interpolate the

fit profile at a higher wavelength resolution than observed by EIS. The

use of these methods are demonstrated in the longer example program below,

which also shows one method for finding the indices and coordinates of

maximum intensity.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import astropy.units as u

from astropy.coordinates import SkyCoord

from astropy.wcs.utils import wcs_to_celestial_frame

import eispac

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Read in the fit template and EIS observation

data_filepath = './eis_20190404_131513.data.h5'

template_filepath = './fe_12_195_119.2c.template.h5'

tmplt = eispac.read_template(template_filepath)

data_cube = eispac.read_cube(data_filepath, tmplt.central_wave)

# Select a cutout of the raster

eis_frame = wcs_to_celestial_frame(data_cube.wcs)

lower_left = [None, SkyCoord(Tx=-25, Ty=225, unit=u.arcsec, frame=eis_frame)]

upper_right = [None, SkyCoord(Tx=175, Ty=425, unit=u.arcsec, frame=eis_frame)]

raster_cutout = data_cube.crop(lower_left, upper_right)

# Fit the data and save it to disk

fit_res = eispac.fit_spectra(raster_cutout, tmplt, ncpu='max')

save_filepaths = eispac.save_fit(fit_res, save_dir='cwd')

# Find indices and world coordinates of max intensity

sum_data_inten = raster_cutout.sum_spectra().data

iy, ix = np.unravel_index(sum_data_inten.argmax(), sum_data_inten.shape)

ex_world_coords = raster_cutout.wcs.array_index_to_world(iy, ix, 0)[1]

y_arcsec, x_arcsec = ex_world_coords.Ty.value, ex_world_coords.Tx.value

# Extract data profile and interpolate fit at higher spectral resolution

data_x = raster_cutout.wavelength[iy, ix, :]

data_y = raster_cutout.data[iy, ix, :]

data_err = raster_cutout.uncertainty.array[iy, ix, :]

fit_x, fit_y = fit_res.get_fit_profile(coords=[iy,ix], num_wavelengths=100)

c0_x, c0_y = fit_res.get_fit_profile(0, coords=[iy,ix], num_wavelengths=100)

c1_x, c1_y = fit_res.get_fit_profile(1, coords=[iy,ix], num_wavelengths=100)

c2_x, c2_y = fit_res.get_fit_profile(2, coords=[iy,ix], num_wavelengths=100)

# Make a multi-panel figure with the cutout and example profile

fig = plt.figure(figsize=[10,5])

plot_grid = fig.add_gridspec(nrows=1, ncols=2, wspace=0.3)

data_subplt = fig.add_subplot(plot_grid[0,0])

data_subplt.imshow(sum_data_inten, origin='lower', extent=cutout_extent)

data_subplt.scatter(x_arcsec, y_arcsec, color='r', marker='x')

data_subplt.set_title('Data Cutout\n'+raster_cutout.meta['mod_index']['date_obs'])

data_subplt.set_xlabel('Solar-X [arcsec]')

data_subplt.set_ylabel('Solar-Y [arcsec]')

profile_subplt = fig.add_subplot(plot_grid[0,1])

profile_subplt.errorbar(data_x, data_y, yerr=data_err, ls='', marker='o', color='k')

profile_subplt.plot(fit_x, fit_y, color='b', label='Combined profile')

profile_subplt.plot(c0_x, c0_y, color='r', label=fit_res.fit['line_ids'][0])

profile_subplt.plot(c1_x, c1_y, color='r', ls='--', label=fit_res.fit['line_ids'][1])

profile_subplt.plot(c2_x, c2_y, color='g', label='Background')

profile_subplt.set_title(f'Cutout indices: iy = {iy}, ix = {ix}')

profile_subplt.set_xlabel('Wavelength [$\AA$]')

profile_subplt.set_ylabel('Intensity ['+raster_cutout.unit.to_string()+']')

profile_subplt.legend(loc='upper left', frameon=False)

plt.show()

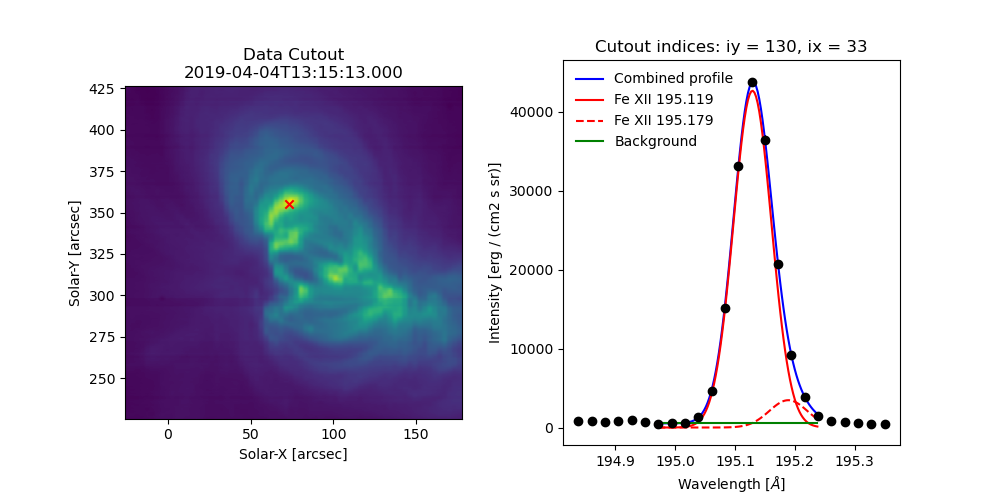

Fig. 5 Example data cutout (left) and fit profile (right) for the spectral window containing the Fe XII 195.119 Å line. The red X shows the location of the maximum summed intensity.

EISMaps for Sunpy

The fit line intensities, velocities, and widths can be loaded into an

EISMap, which is a subclass of sunpy.map.Map. This allow

us to leverage the full power of Sunpy to do all sorts of cool science like

comparing spacecraft locations, co-aligning images, reprojecting maps, and

performing field extrapolations (see the Map sections of the SunPy

User’s Guide and

Example Gallery

for some demonstrations). You can get an EISMap by either

using the get_map method or saving the

measurements to FITS files using export_fits and then

loading them in with either eispac.EISMap(FILENAME) or even

sunpy.map.Map(FILENAME) (assuming EISPAC is also imported in your

program).

For now, we will just show you some examples of the quick-look plots.

>>> # Fit intensity (in a nice sunpy Map)

>>> inten_map = fit_res.get_map(component=0, measurement='intensity')

>>> inten_map.peek()

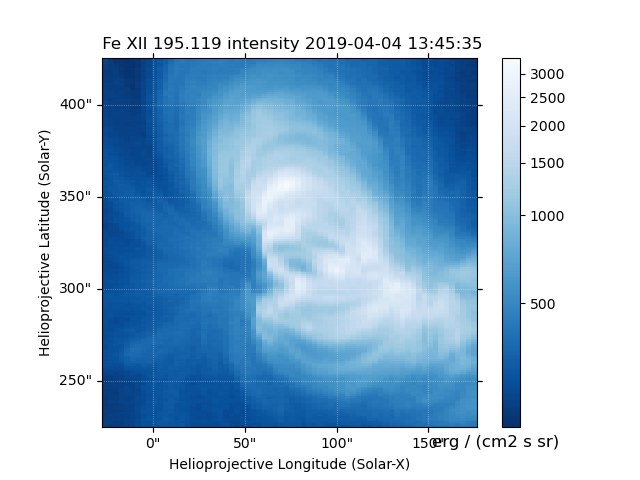

Fig. 6 Fit line intensity in a nice SunPy Map.

>>> # Fit velocity map

>>> # Note: You can also use positional arguments and abbreviations

>>> vel_map = fit_res.get_map(0, 'vel')

>>> vel_map.peek()

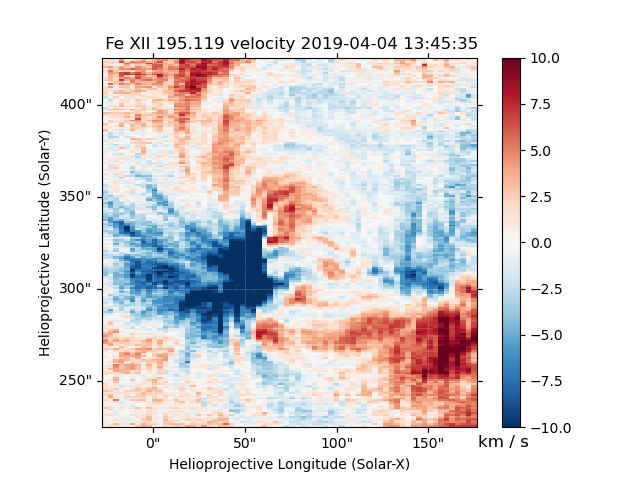

Fig. 7 Fit line velocity map.

Attention

While we have corrected the velocity maps for orbital effects, there are still some unknown uncertainties. This is largely the case for ALL EIS velocity maps, not just those computed by EISPAC. Please use with care.

Footnotes